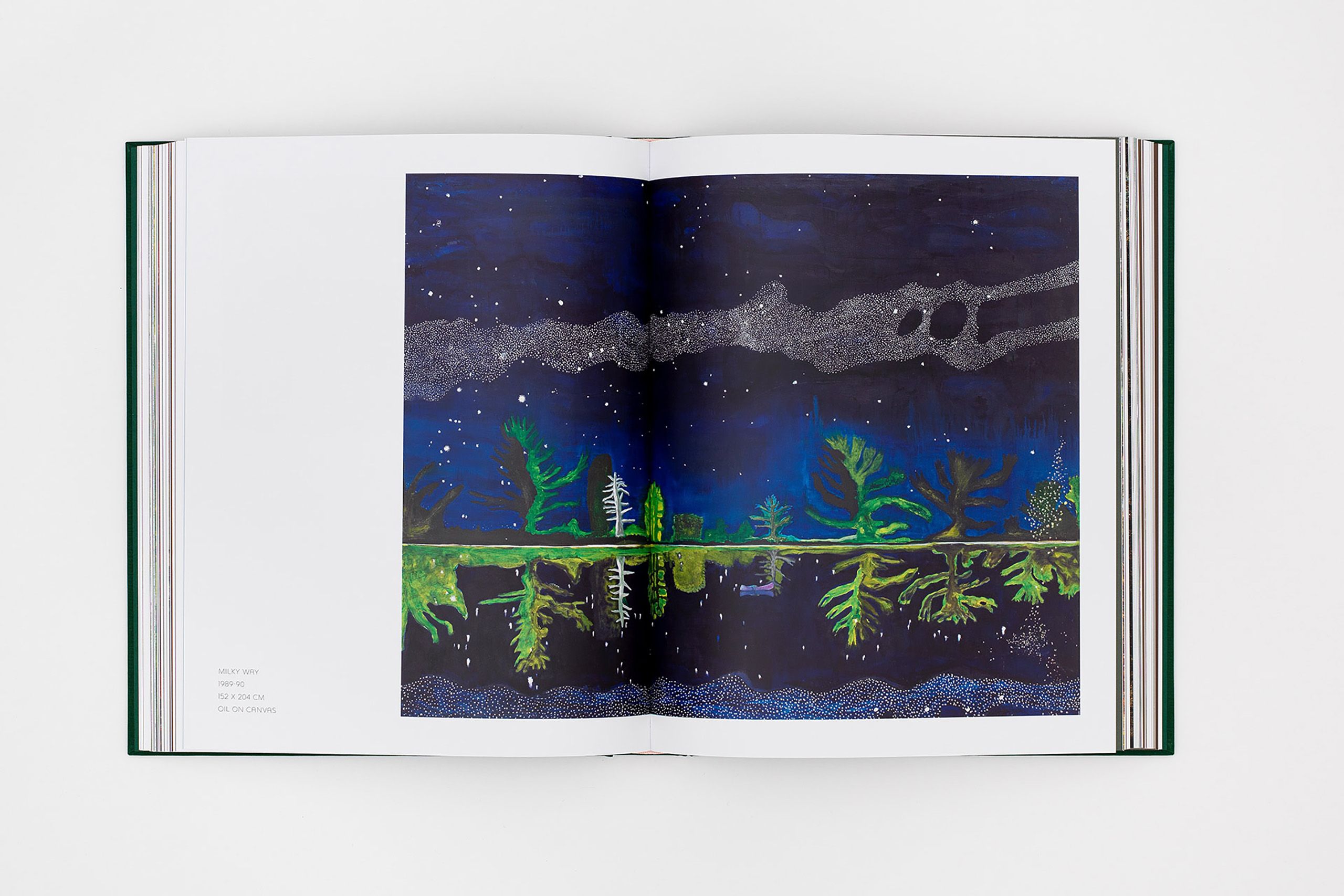

“Man stands face to face with the irrational”, wrote Albert Camus. “He feels within him his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.”

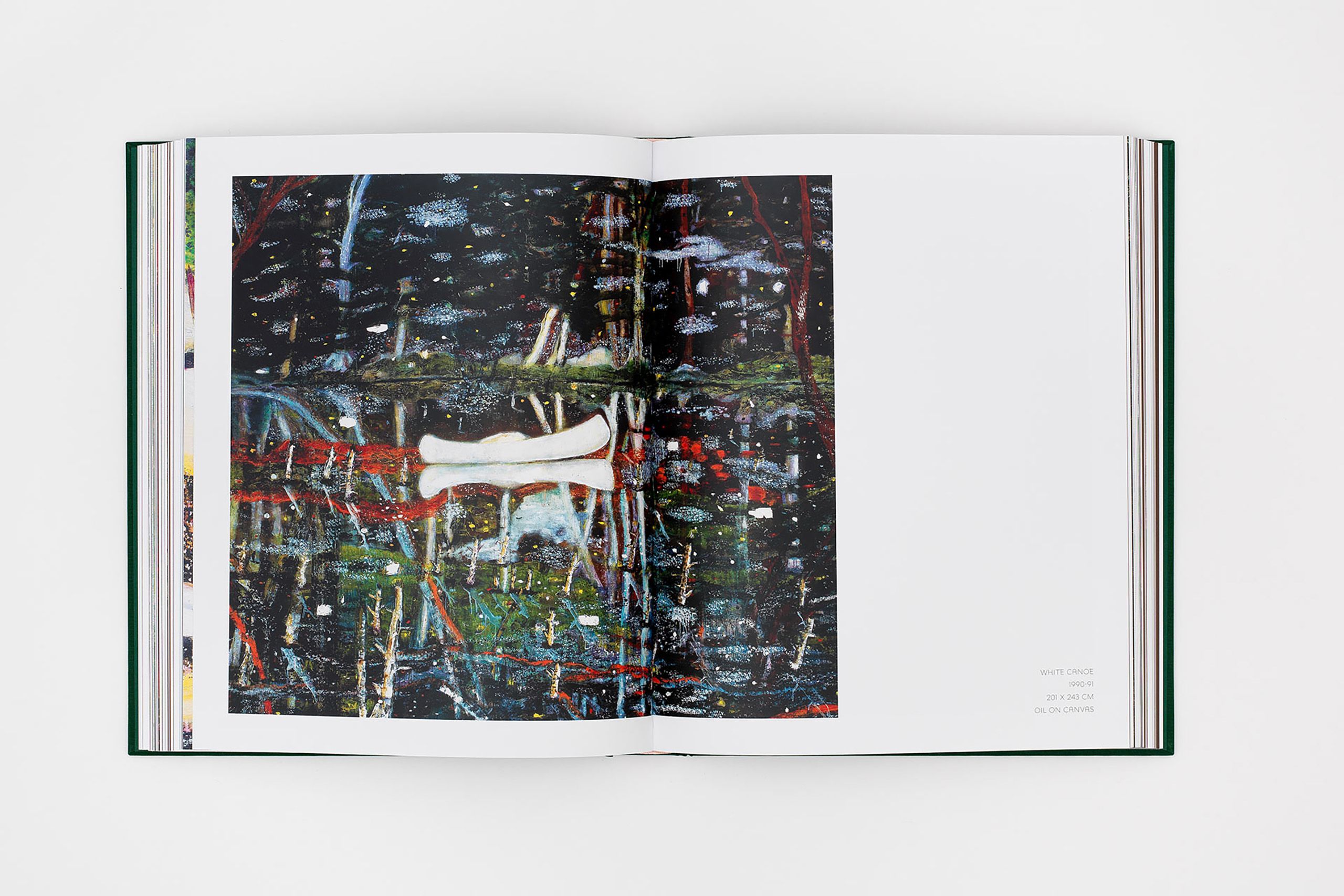

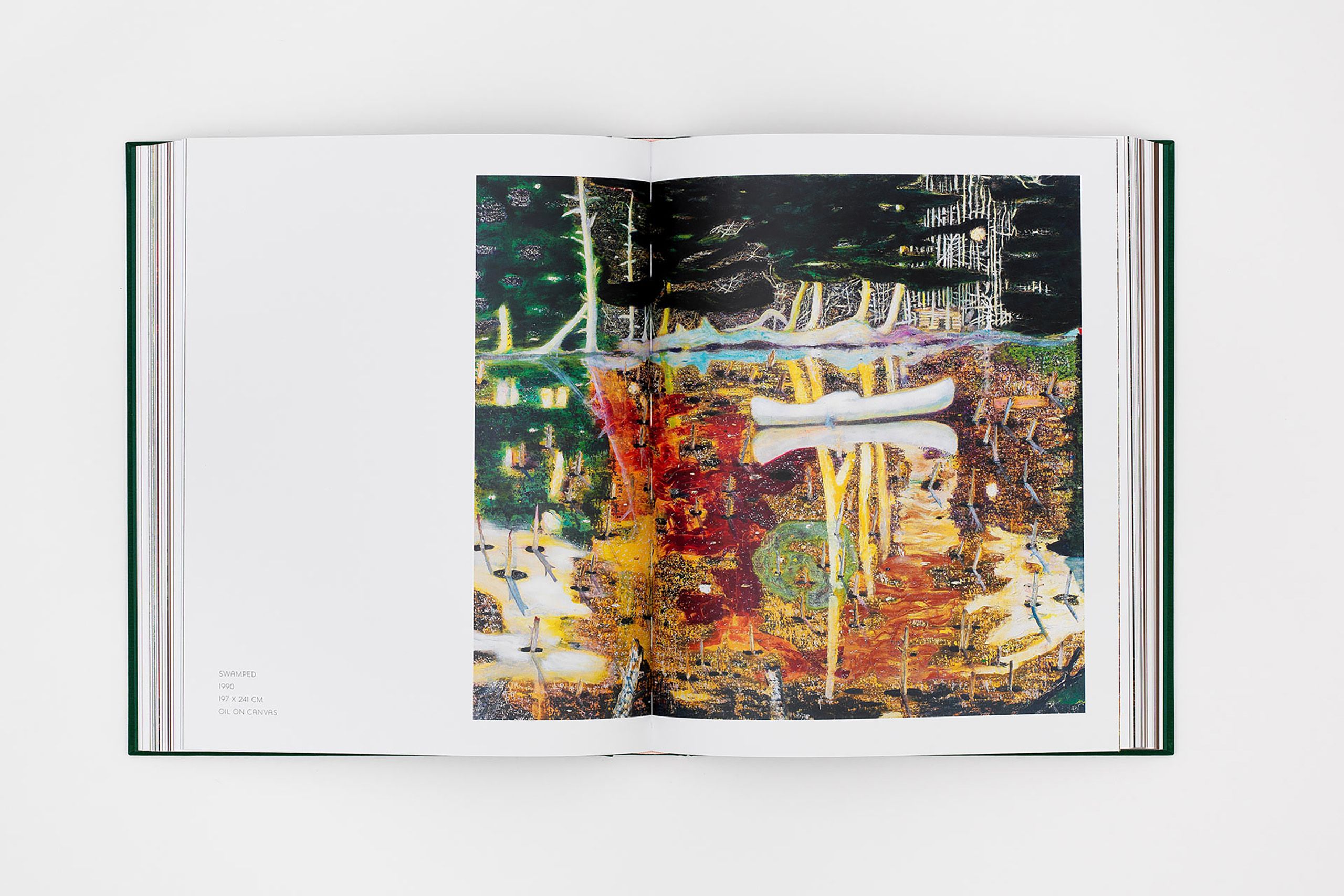

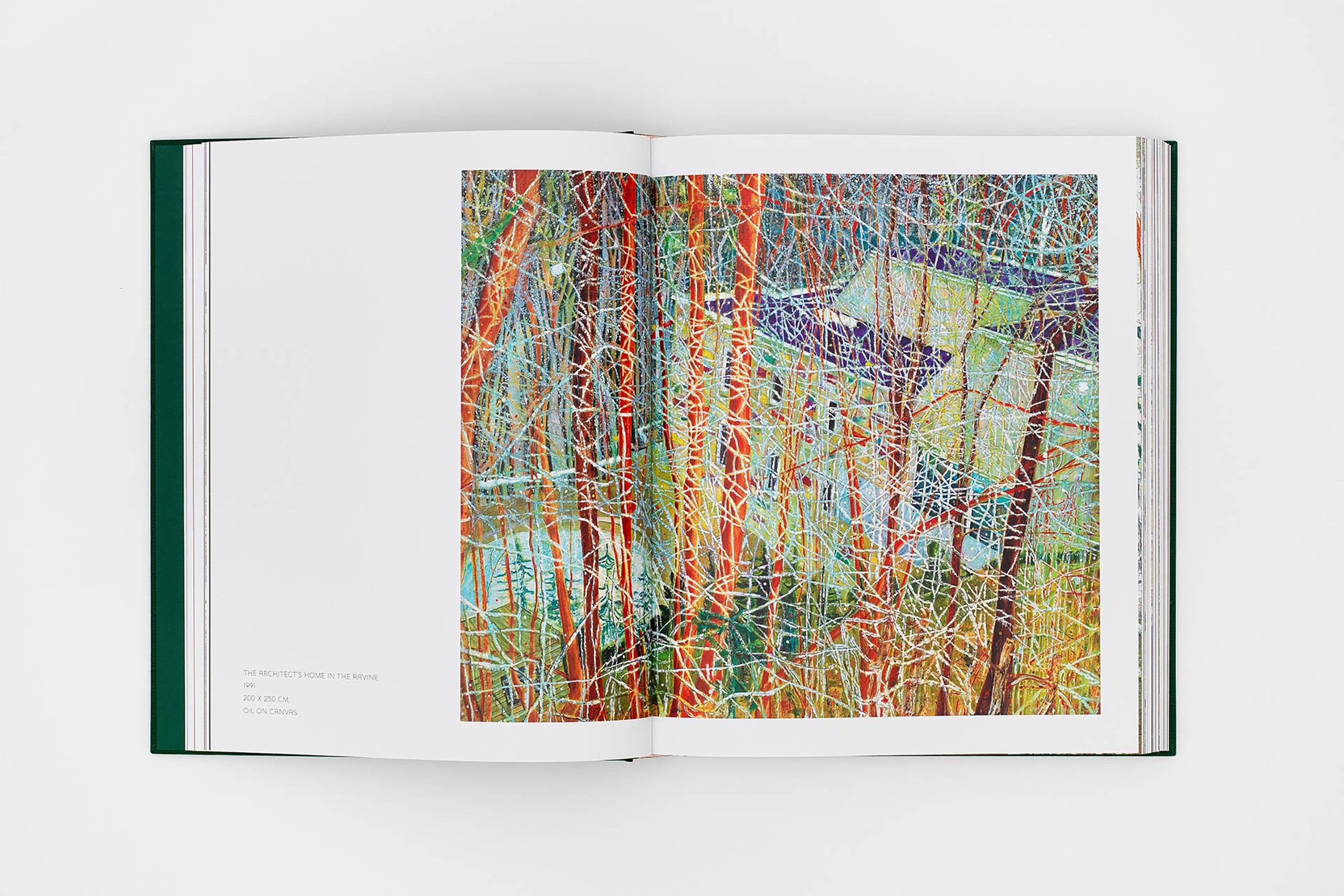

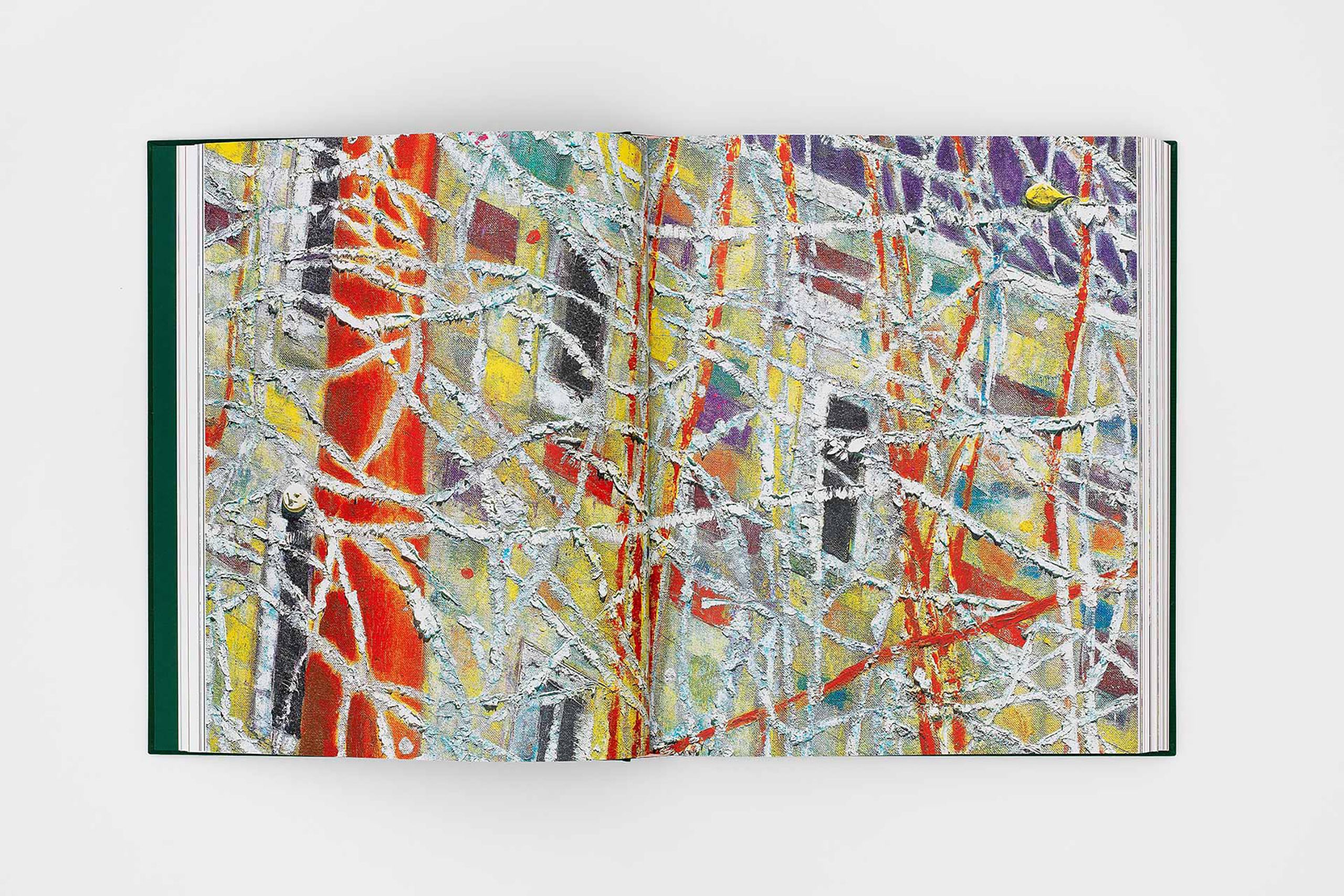

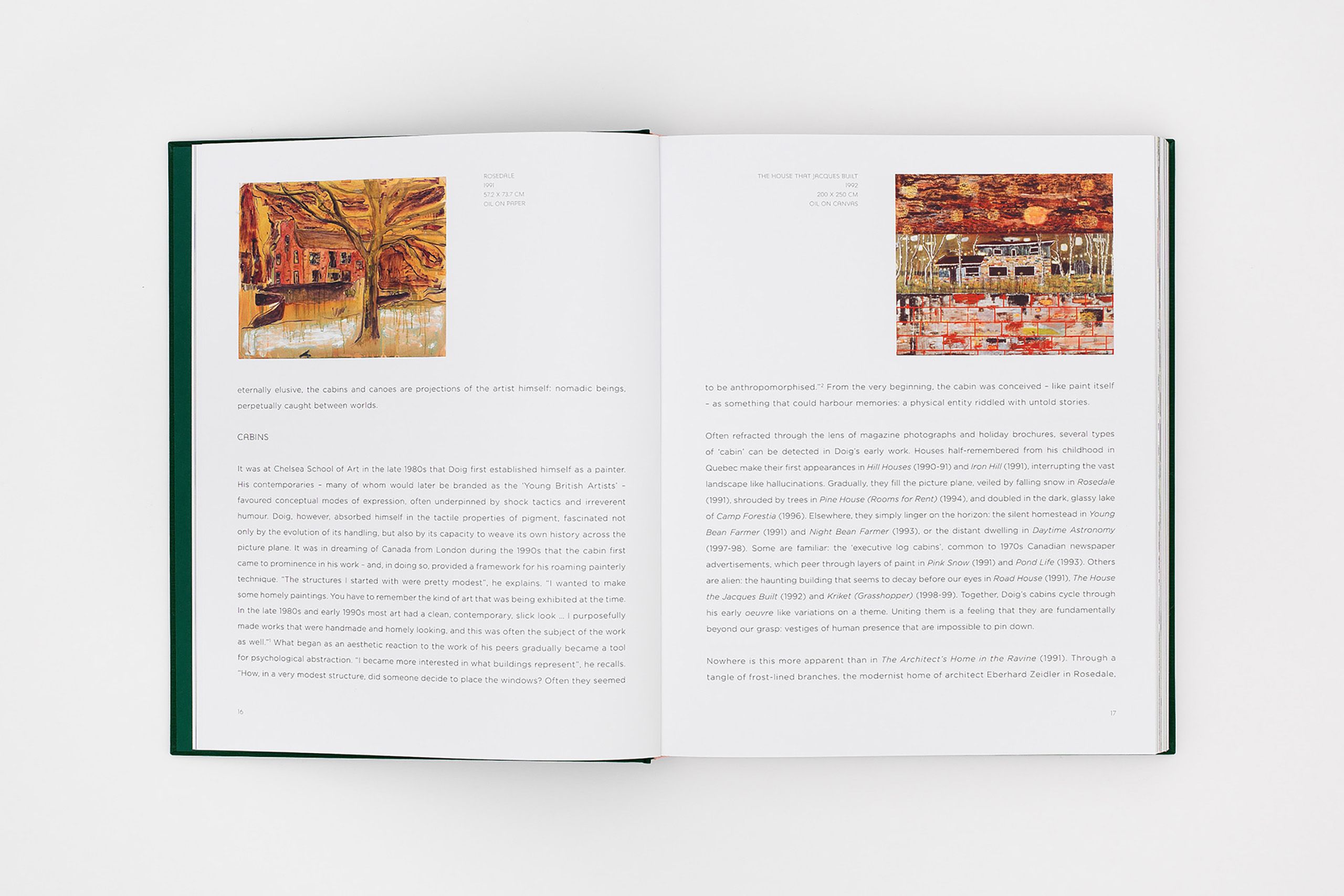

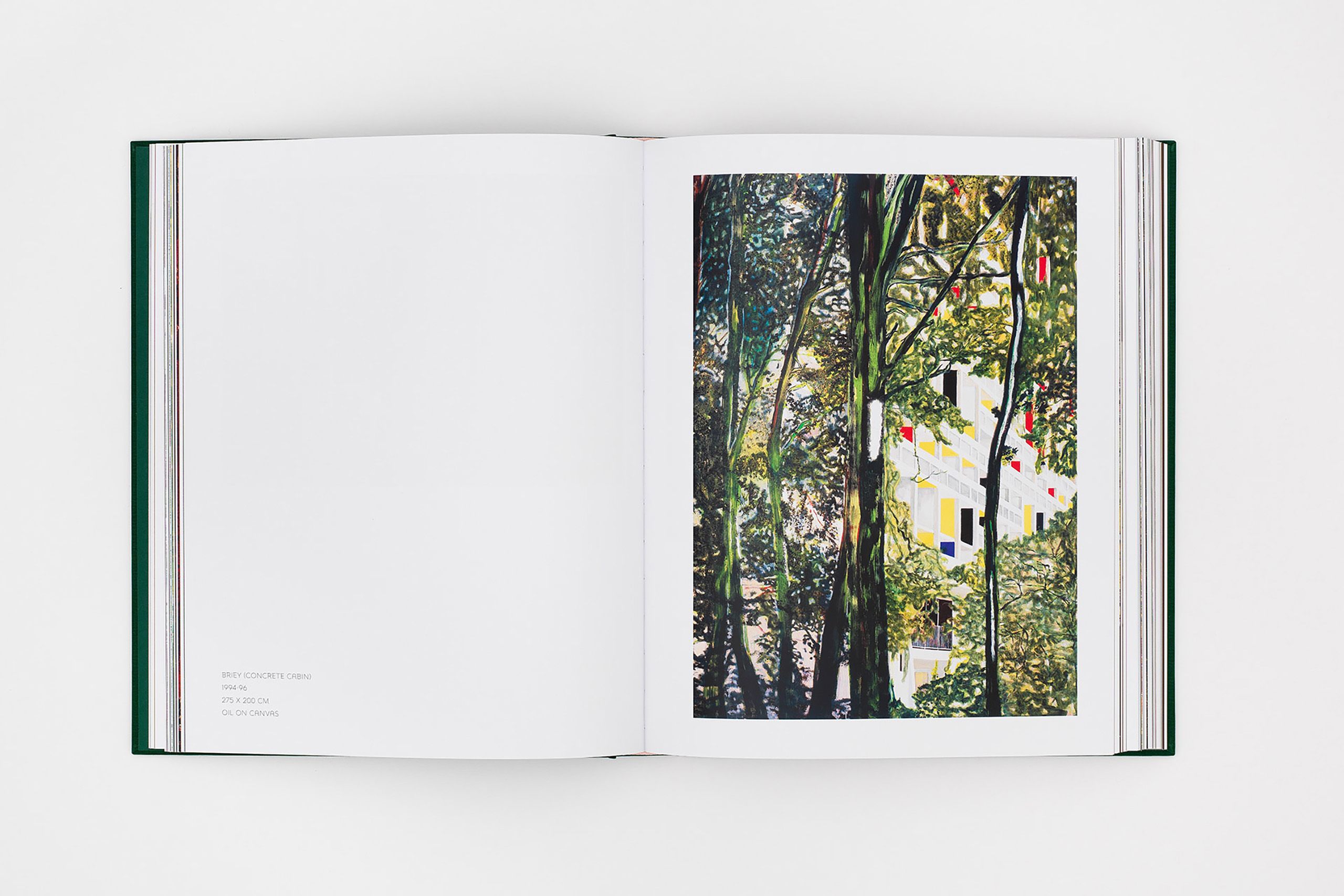

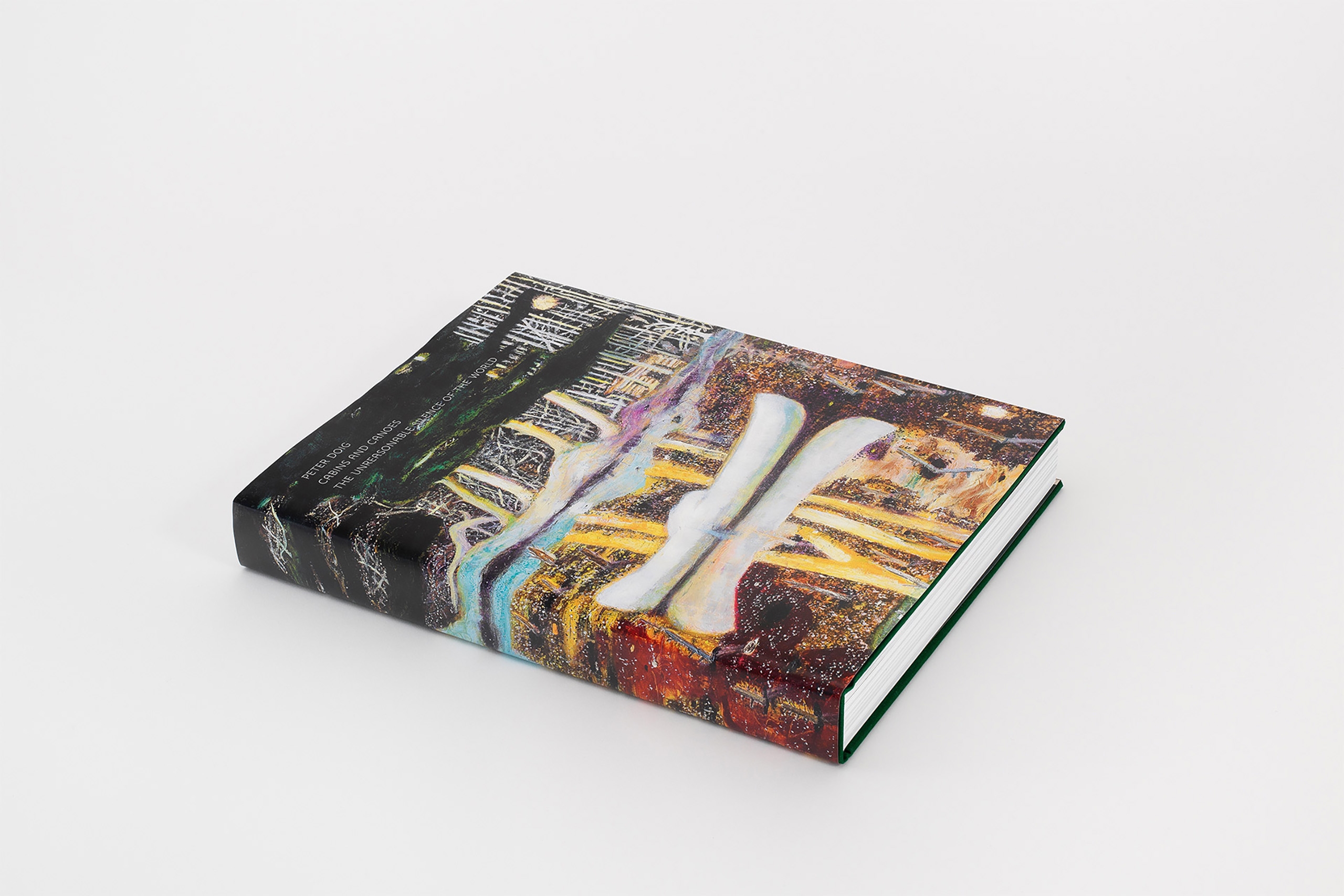

Doig’s disjointed past lies at the heart of his work. It finds its keenest expression in two persistent strands of imagery: the cabins and canoes. Together, like recurring reveries, they chart the wanderings of his psyche. The canoe drifts silently between tundra and tropics. The cabin lies dormant in dense pine-scented thickets, veiled by blizzards and branches. Like talismans, they quiver beneath shimmering membranes of colour, or lie submerged within tangled tendrils of paint. Their forms emerge from abstract swamps of pigment, only to dissolve again in the blink of an eye. Suspended within lonely backwaters and ravines, they are dreamlike projections of foreign lands: of places half-forgotten and re-imagined from afar.