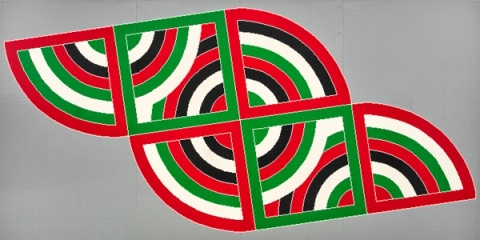

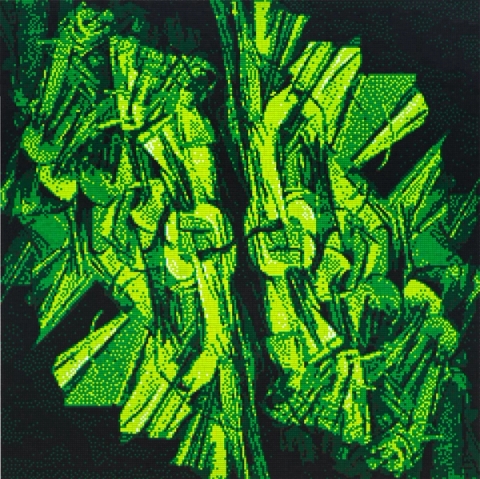

During his time in New York in the 1980s, Ai was influenced by the avant-garde legacy of Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades” and the serialized, factory-like use of images in Andy Warhol’s work. These influences are present in Ai’s new works, which are made by hand from thousands of toy bricks. Playful yet sharp, the works engage with serious matters. They raise questions about technology and authorship while emphasizing the accessibility and mutability of cultural images in the digital age.

Ai Weiwei began using LEGO bricks in 2014 for his exhibition Trace, at Alcatraz Prison in San Francisco. Since then, toy bricks—both LEGO and the Chinese equivalent WOMA—have become an important medium for the artist. For What You See Is What You See, Ai presents twelve large-scale toy brick works that subvert traditional narratives and techniques, addressing freedom of expression, geopolitical conflicts, and Western iconoclasm. The exhibition’s title refers to a seminal statement by the late American artist Frank Stella, inviting us to reconsider how we perceive and interpret both historical and contemporary forms.

The versatile use of toy bricks brings to mind pixels in digital images and historical traditions of tile mosaics. Each brick functions autonomously, yet contributes to a larger image, mirroring individual roles within society—a theme Ai has explored in earlier works like Sunflower Seeds (2010).

Through satire and unparalleled craftsmanship, Ai Weiwei democratizes art to make complex conversations more accessible. The exhibition opens with The End, the closing title of Charlie Chaplin’s film The Great Dictator (1940). The work suggests a new chapter, encouraging viewers to reflect on the complexities of today’s global landscape as they walk through the show.

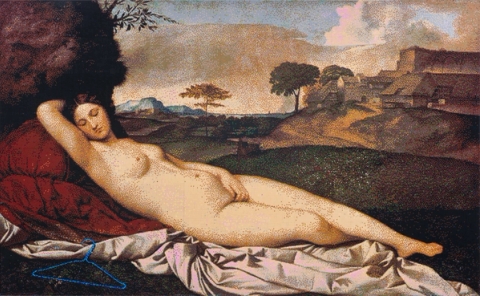

Several works reinterpret iconic masterpiece paintings, drawing from pivotal moments in art and history. Ai incorporates personal and political symbols into the historical imagery, transmuting context and creating new meaning. By inserting a dark void into Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (1914–1926), the artist reflects on his childhood in exile as well as the 81 days he spent in detention by Chinese authorities without formal charges in 2011.

Ai’s concerns with displacement and belonging are further explored in Party, an iron sculpture from his Roots series, which is inspired by his father Ai Qing’s poem about underground networks of trees and the deep connections between nature, history, and humanity. The eternalized form of three roots joined together symbolizes both environmental and human catastrophe and nature's boundless potential for new beginnings.

Combat Vases, an installation of 90 porcelain helmets, references Germany’s January 2022 offer to send 5,000 helmets to Ukraine, which was widely mocked as insufficient. The installation reflects on the lives of soldiers and civilians caught in conflict, while criticizing symbolic political gestures.

What You See Is What You See is not a single political statement or easy answer. Instead, the exhibition is a reminder of the role art plays in fostering reflection and critical thought, urging us to question the forces shaping our world and our own roles within them.

“We do not know what the future holds. Based on our current experiences, regardless of whether they seem prophetic or wise, it is very difficult to determine how to respond to today’s realities or to anticipate tomorrow’s events. Therefore, my most sincere advice is not to believe too firmly in anything."

Ai Weiwei - 2024

Ai Weiwei interviewed by Jane Ursula Harris: At a time when dialogue in the art world is increasingly fraught and polarized, especially where “politics” are concerned, the ability to have a deeply thoughtful conversation with Ai Weiwei—one of the world’s most prominent artist-dissidents—feels like a momentous occasion. Centered around the works on view at Faurschou, our exchange considers the role of art history, consumer readymades, poetry and nature, among other prevalent themes that have long defined Ai’s practice. What emerges is an artist who still puts activism ahead of fame, and whose dedication to civility and grace embodies a generosity the world is in dire need of.

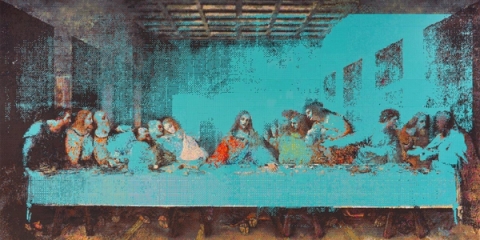

JUH: In your work The Last Supper in Turquoise, 2022, made after Warhol’s version of the canonical Da Vinci original, you replace Judas with an image of yourself. In various interviews, you’ve shared that your father told you the story of Judas when you were a child, and the impact it had. The figure of Judas is such a powerful archetype of betrayal yet also a symbol of fate (without his betrayal, Jesus would not have saved the world from sin). Alluding to this fateful role you recently said, “I put myself as Judas because I want to tell people not to trust me.” In some ways I interpret this as a disavowal on your part to be a reliable narrator that people in the art world can turn to for moral certitude. That in essence you are saying such faith in any single person is misguided. Can you offer more thoughts about what you meant by that statement in terms of context and thinking?

AW: When discussing culture—including the understanding of religion and the definition of civilization, as well as the many facets of aesthetics, ethics, and philosophy—no matter how we approach these topics, it is always through narrative. This amplifies art's role in human thought and its essential reason for existence. Narrative itself, whether it involves justice, truth, error, or even evil, flows along with the relentless, ever-changing current of time, continuously shifting in perspective and context. As these shifts occur, our judgments may crumble, sink beneath the surface, or emerge anew. When I say that if there is meaning, it lies in not believing in meaning, it is because meaning only holds when its emergence is certain; through the change of context or time, meaning itself fades away or loses the foundation upon which it was constructed.

The time I have experienced is, in fact, a period of self-subversion and irony. From my early years of exile with my father to growing up under a collectivist, autocratic regime, and later spending 12 years in New York, I then returned to a rapidly transforming China, characterized by a new form of nationalist capitalism in an era of opening up. When China's engagement with the cultural orders of Europe and the US led to increasing contradictions and conflicts, I moved to Europe. These changes were neither controllable nor predictable, much like many events occurring today. We do not know what the future holds. Based on our current experiences, regardless of whether they seem prophetic or wise, it is very difficult to determine how to respond to today's realities or to anticipate tomorrow's events. Therefore, my most sincere advice is not to believe too firmly in anything.

JUH: There are several works in the Faurschou exhibition that reflect your interest in art history as both a resource and a readymade. One of my favorites, After The Death of Marat, 2019, quotes not just the 1793 Neoclassical original by Jacques Louis David (itself a take on the Entombment of Christ by Caravaggio, 1603), but seemingly a contemporary work by the Chinese artist, He Xiangyu. The latter, made in 2014, presents a fiberglass life-scale depiction of your body lying face down on the floor that was so convincing some thought it was a real corpse. Your appropriation also invokes the viral photo of the two-year old Syrian boy, Alan Kurdi, whose drowned body was found on a Turkish beach. This connecting of the persecution of dissidents to the plight of refugees, evident as well in your 2016 recreation of that photo using your own body, is a powerful aspect of this work. Can you talk more about your personal relationship to these images and the conflation of yourself with Marat and the Syrian boy—of art history with viral politics?

AW: Thank you for your detailed exploration of this artwork. Your understanding of its background is impressively thorough. What I can add is that when an event or individual appears within a particular context, people are inevitably drawn to make connections with similar phenomena. Regardless of the artwork's title or its relation to the image of Alan Kurdi’s photograph, including my own situation and that of all refugees, the imagery of being cast into the sea and washed ashore compels us to associate an individual's experience with the broader history and fate of all people. This type of connection is inherently tied to symbolism and implies a kind of suggestion or hypothesis; as an image, it carries a prophetic quality and an undeniable certainty. In relation to my playful use of toy bricks as readymade objects, this approach creates a piece that navigates the path of absurdity and chaotic reality. The 2D work maximizes the interplay of history, personal experience, and reality, all of which are embedded within the information conveyed.

JUH: Do you see the work—or any that feature you—as a kind of “self-portrait”?

AW: We can put it that way since as mentioned, I am someone deeply marked by the characteristics of my era—an era that is so clearly fractured and divided.

JUH: The Legos and WOMA toys you use to build these works obviously evoke associations with childhood play and consumer culture—in addition to mosaics and pixels—but they also represent a larger goal in your work to blur distinctions between “past and present, hand and machine, precious and worthless, construction and destruction.” What do these boundary blurrings accomplish for you as an artist?

AW: First of all, I make artworks in toy bricks to respond to the general conception of artists as individual creators with their own taste, techniques and habits that are shaped through training and thinking. As a children's toy, these bricks have the potential to liberate people from such conventional forms of skill and training. Whether through pixelation or pointillist, mosaic-like techniques, artworks in toy bricks significantly "de-art" the process—stripping away the kind of personal style traditionally considered to be the defining and most valuable aspect of an artist’s practice. The toy bricks reflect instead an era characterized by consumerism, fleeting entertainment, and superficial media culture and as such embody for me the new, standardized language of globalization. This new language shapes all cultural products, whether they are created by artists, consumed by viewers, or curated by cultural institutions, replacing spaces for thought and expression that were once characterized by high individuality.

JUH: So are you saying that the idea of artists as individual creators is something you reject as irrelevant

in this era, or are you simply observing its limits?

AW: The notion of so-called artists as independent creators in the West has been overstated. Yes, art is indeed an independent and personal endeavor, distinct from science, but this independence and so-called individuality are often deeply influenced by the marks of our time. If I say I reject this mode of creation, that in itself represents a new form of independence. The original idea of individuality and independent creators carries significant limitations. True independence can only exist when one challenges and rejects these confines. This form of existence differs from what is typically regarded as independence.

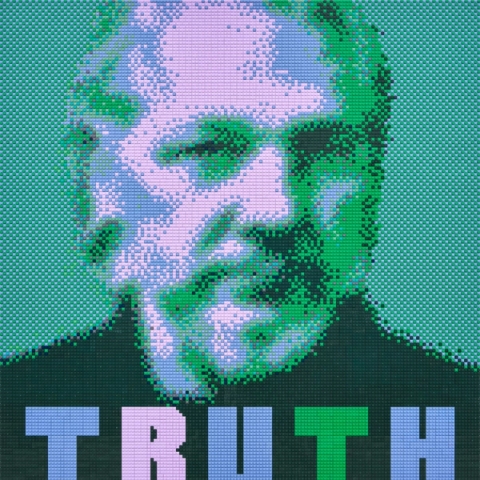

JUH: The interchangeable nature of the Legos units also troubles ideas of the individual versus the collective, of hierarchy versus order. At a time when the world is desperate for public figures they can trust, how can artists effectively challenge the voice of global authoritarianism?

AW: Toy bricks are a type of game that embodies both self-elimination and self-regulation, whether the pieces are assembled together, as intended, or scattered apart. Each individual unit retains its own distinct characteristics yet functions in relation to a whole. Artists who discovers a precise language that aligns with their own life experiences and thought processes, that harmonizes with their own thinking, and attitudes about the world can better resist the cacophony of existing noise and assert the truth of their existence. To do so, one's language must first stem from a genuine affirmation of one's understanding of self as part of the larger landscape of contemporary human culture.

JUH: This is so true, especially for artists who, like you, who engage materials as a language that can carry allegorical - conceptual and philosophical - meaning while still remaining connected to the realm of “now”. Your work has often made a bridge to a non-art world, to an audience that may or may not be familiar with contemporary art through its references to the political and social circumstances that shape our lives. How much do you think about your audience, and does it shift with the kind of work you make?

AW: I often seek to work with readymades or materials that people are already familiar with, whether it’s porcelain, toy bricks, or bamboo. Because I believe these mediums carry an inherent emotional connection with the public—one that is often much stronger than we might imagine. By taking something fixed and familiar and making subversive adjustments, the impact of the transformation becomes immediately apparent.

JUH: We are living in an Anthropocene era that’s been characterized as apocalyptic yet many people in the Global North continue to live lives of great excess, continuously pursuing comfort and convenience at all costs. Many younger people feel so hopeless in the face of this collective denial that they no longer believe there is any possibility of preventing the dire consequences of climate crisis. You’ve addressed the latter in various ways, but your use of trees is particularly resonant for me as I’ve always regarded them as sacred beings. I often think that animist traditions, which imbue the natural world with spiritual immanence, are the key to a returning humans to a more harmonious relationship with nature. I know that you have worked with trees since 2009, collecting the remains of ancient trees felled for construction, and re-assembling them in sculptures that bring them back to life. What do you think trees can teach us?

AW: Wood, like air and rock, is an essential part of the Earth's natural family. Trees, with their own life force, grow resiliently in nearly any environment or temperature until they encounter the destructive impulses of humankind. Despite this, trees remain the quietest of witnesses, contributing immensely to Earth's ecosystem and human activity. My personal interest in trees is rooted in my father's generation. In fact, the cover of my father’s first poetry collection featured three trees he drew himself. Later, in the 1980s, when his reputation was officially restored, his first post-rehabilitation poetry collection featured a forest, this time drawn by me. Though trees are silent, their life, the oxygen they produce, and their impact on the climate make Earth a habitable place for all living things.

Trees, like everything in the world, serve as a reminder of the parallel existence that attests to human life. If we fail to grasp that human beings are transient and that our journey is fleeting, our understanding of life becomes skewed. Trees, in particular, through their growth patterns, their connection to nature, and their relationship with the planet, constantly remind us of the fragility of humanity and the limitations of our understanding.

JUH: I am sure you saw the recent news that artist Gao Zhen—half of the artist duo known as the Gao brothers—was recently detained on a visit to China, charged with slander under the Heroes and Martyrs Protection Law. The artworks in question, which predate the law, include sculptures lampooning Mao from the duo's 2007 Miss Mao series. Its ironic given that these artists are known internationally for their work on radical empathy and the healing power of embrace, which they’ve enacted through public performances staging hugs between individuals. Do you think the Chinese government will ever stop persecuting those who criticize(d) the Cultural Revolution?

AW: I believe that a country’s approach to art and free expression during its development reflects its broader value systems and its stance on aesthetics and ethics. The brutal suppression of artists—whether by China or other repressive regimes—always reveals how far a society has to go in its journey toward civilization. Such transformation must be grounded in respect for human beings and artistic freedom. I believe that every country, like every organism, undergoes its own process of development. In reality, there are no universal standards. The West often attempts to abstract certain values, and this abstraction itself reflects obstacles to understanding and a tendency to go against nature. The process of development is like a seed, with different stages of growth and vastly different forms. For people, this process involves one's stance and attitude.

The End, 2024

Toy bricks (WOMA)

240 x 320 cm

Bjarne Melgaard

Barney Does It All