Highlighting works by Louise Bourgeois, Miles Greenberg, and Yoko Ono, the exhibition revolves around physical and metaphorical aspects of the embrace: From embrace as the merging together of bodies, to embrace as an act of acceptance and shelter or by contrast as claustrophobic smothering. Through performance, installation, and sculpture, myriad facets of the embrace are unfolded in three galleries, one dedicated to each artist.

Directed by Scott D. Keenan © Faurschou

In Miles Greenberg’s performance The Embrace, two performers, blinded by white contact lenses, sit on a large rock in a glass cube. Meeting for the first time, the two lock in an intimate embrace, gradually coalescing into one sculptural form. The amalgam of the two figures is reflected from below by a pool of saltwater. Overhead, a steady drip of fresh water quietly feeds into the reservoir, disrupting the reflective surface. The two waters fuse invisibly, like an estuary enclosing the couple’s feet.

With this enfolded composition, Greenberg turns the two bodies into a monument for the audience to study. The performers’ white contact lenses act as a barrier between the performers and the viewers’ gaze, drawing attention to the physical experience of the shapes and spaces appearing in the embrace.

In The Embrace, performers extend a familiar gesture into sculptural eternity. Movement – if any – is barely visible to the viewer. Greenberg’s work often isolates elements of the body or body movements, and in The Embrace, it is monumental stillness that challenges our perception of time and space. The work immerses viewers in rhythms and complicity and a consideration of the physical and spiritual exchange of an embrace.

The performance is live on Saturdays from 1–7 pm.

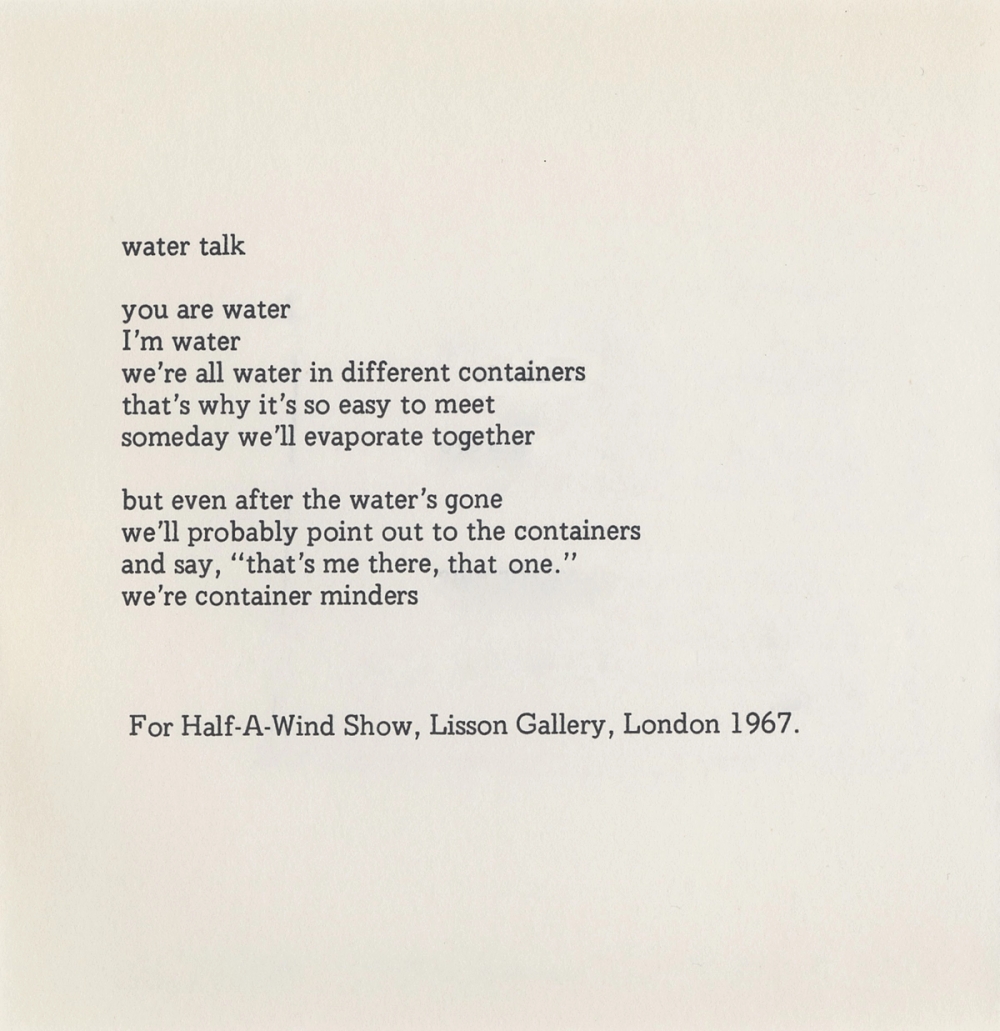

Yoko Ono is known for her ability to take on the complexities of the world through her art, which engages the viewer and lets them reflect upon their world. In this exhibition, two of the artist’s installation works, We’re All Water and Ex It, are juxtaposed.

The first work is made up of a row of identical glass bottles of water, each labeled with the name of a person, from artists, musicians, and philosophers, to dictators, freedom fighters, and comedians, among others. The work is a reminder of what fundamentally unifies us regardless of status, impact, and name. Water has been a recurring theme in Yoko Ono's oeuvre, which she uses to emphasize our commonality despite our differences. This version of “We’re All Water” was originally exhibited in Beijing, China, and the labels were written in Mandarin. The original list of names (in translation) for the Beijng version of We’re All Water is included below.

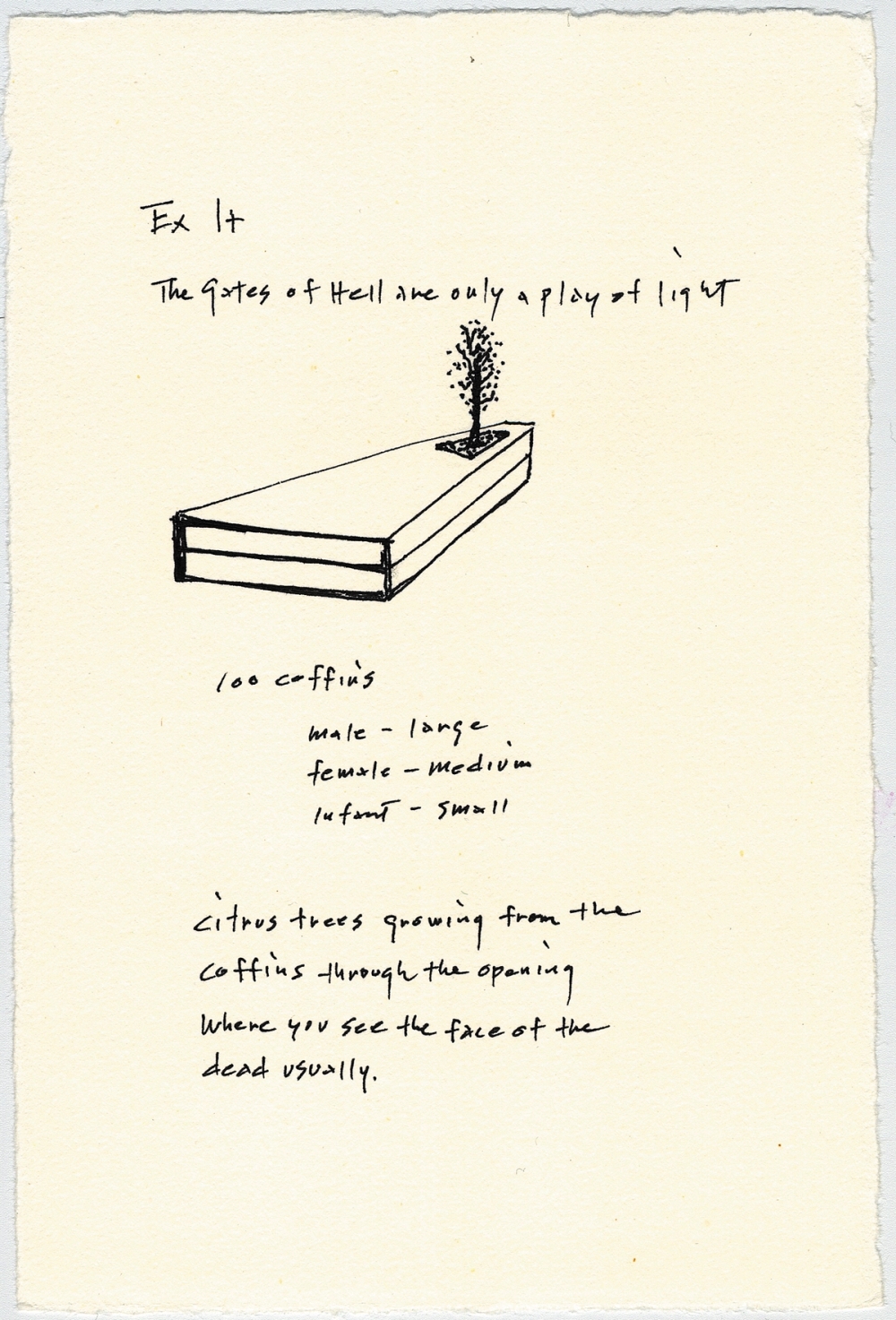

In Ex It, the viewer is met with birdsong, amidst rows of wooden coffins in which trees grow from “the opening where you see the face of the dead usually.” Yoko Ono shows us that there is always hope present.

Yoko Ono

Ex It (Beijing version)

1997/2015

100 wooden coffins, living trees, sound

A drawing by Yoko Ono for the original version of Ex It, Valencia, Spain, 1997.

Yoko Ono

We’re All Water (Beijing version)

2006/2015

118 glass bottles and water

Louise Bourgeois grasps inner conflict by expressing herself through tactile sculpture. In her work, introverted references nevertheless become universal subjects, recognizable to most. To Bourgeois, the embrace is of a shielding character, but as well-intentioned as this act of protection might be, just as insulating or even suffocating it can feel.

In her work, Fée Couturière (Fairy Seamstress) the title refers to the tailor bird, which uses found objects in its nest-building. The sculpture resembles a hanging bird’s nest perforated by many gaps and passages. The sculpture – without any clear entrance or exit – confuses and wards off any intruders, safeguarding its inside like the bird shields its offspring. Louise Bourgeois has said that for her the work is a self-portrait, and that the interior passages reflect the many emotional states of the self, but also that the work represented a place where one can hide from the outside world and find shelter and solace.

In Hanging Janus, the double-sided nature of the embrace, as with many things, are underlined. The sculpture is at once both masculine and feminine. It can spin, since it is one of Bourgeois’ hanging pieces. The woman/mother and the man/father are united or forced together into the same sculpture yet remain separate entities. Janus is the Roman god of all beginnings; his face is often depicted on city gates looking both into and out of the town. The twin faces enable him to look both forward and backward at once – to look into the future and the past.

Avenza Rrevisited and Forêt (Night Garden), embodies one of the central themes of her career—the relationship between the individual and the group. In her sculpture, Bourgeois recreates the complicated dynamics of group behavior and identity. A few of the forms seem to stand alone, while others fade into the anonymity of the crowd. As Bourgeois once stated, “The relation of one person to [his or her] surroundings are a continuing preoccupation. It can be casual or close; simple or painful or imaginary. This is the soil from which all of my work grows.”

The same theme carries on in C.O.Y.O.T.E. The legs is a memory from Louise Bourgeois’ own childhood sitting beneath the kitchen table, watching the legs of her parents cooking. But the legs can be seen as both a harmful protective space for a child and a barrier to keep one from the rest of the group. Originally this work had the title The Blind Leading The Blind, referring to a painting by Pieter Bruegel, the Flemish Renaissance painter who is known for his often caricatured paintings of peasants and was painted in black and red. But in 1979 the work was painted pink and renamed with the initials of the slogan “Call off your old tired ethics” used by a collective of prostitutes who were fighting for the rights of sex workers. By renaming the work, Bourgeois demonstrated her sympathy with the prostitutes, and compared their conditions to the original meaning of the work: that even if you cannot see anything you will be able to meet the challenges by supporting one another.

Curtis Barnes Sr.

We Wear the Mask